Tag: Texas Route 66

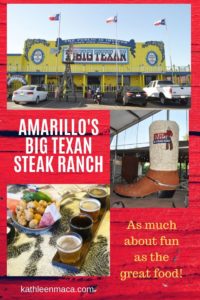

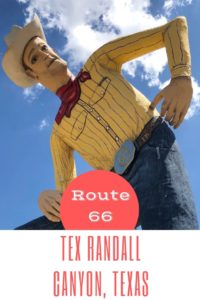

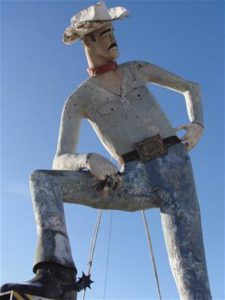

Long, Tall Tex Randall Rides Again

If you think you have trouble finding clothes to fit, just be thankful you aren’t a 47-foot tall cowboy!

You’ve heard the saying that everything is “bigger in Texas,”

“Tex Randall,” the 47-foot tall, seven ton statue in Canyon, Texas was designed and built in 1959 by Harry Wheeler (1914-1997) to draw Route 66 tourists to his Corral Curio Shop and six-room motel. Wheeler, an industrial arts teacher, spent ten months forming the lanky cowboy out of six-inch wire mesh, rebar and concrete.

And here’s the really amazing part…

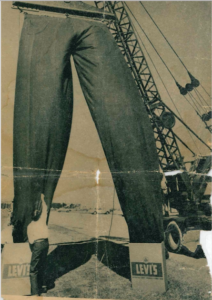

Though his clothes are painted on today, they weren’t originally! Tex’s first Western-style shirt was made by Amarillo awning, using an impressive 1,440 square feet of material. Wheeler sewed it closed in back with sailboat thread, and created sheet aluminum snap buttons and a belt buckle the size of a television screen.

Levi Strauss’ nearby plant made real jeans for him that had to be sewn onto the statue on site. The pants were lifted into place with a crane, and Wheeler stood below, adjusting the “fit” and sewing them together. How’s that for a tall tailor order?

Tex’s boots and features were painted onto the surface of the statue, and he was crowned with a Stetson style hat.

As far as relics from the Route 66 heyday, this tall Texan definitely fits the bill. He became one of the roadside attractions that people would drive miles to see and photograph.

Due to reconstruction of the highway, business at his shop and motel declined. That and personal business caused Wheeler sold the property in 1963. He refused offers to buy Tex that came in from Las Vegas and businesses along Route 66, preferring that his labor of love remain in Canyon.

The following decades of Panhandle winds and weather shredded the figure’s fabric clothes; a semi-truck crashed into his left boot and the original cigarette was shot out of his right hand. The elements sandblasted away large portions of his skin, and his concrete fingers began to crumble.

An Amarillo area businessman purchased Tex with the intention of moving him to his business, but gave up when he learned it would cost $50,000.

In 1987, local community leaders began a “Save the Cowboy” campaign and raised the money to restore Tex. The no longer socially acceptable ci garette in his hand was replaced with a spur, new clothes were painted on to replace the lost fabric set, and he was given an 80s-style moustache.

garette in his hand was replaced with a spur, new clothes were painted on to replace the lost fabric set, and he was given an 80s-style moustache.

By 2010, it became apparent that a more thorough restoration of the statue was needed, and the Canyon community and Canyon Main Street volunteers rallied to save the icon.

The Texas Department of Transportation stepped in to help and set aside almost $300,000 to turn the land around Tex’s boots into a park.

Tex’s cameo appearance in the 2015 Sports Illustrated swimsuit issue provided the exposure to increase interest in the project. After six years of fundraising and work, the project was completed in December 2016, and Tex received his own Texas State Historical Marker in 2017.

Tex’s cameo appearance in the 2015 Sports Illustrated swimsuit issue provided the exposure to increase interest in the project. After six years of fundraising and work, the project was completed in December 2016, and Tex received his own Texas State Historical Marker in 2017.

Tex’s appearance now more closely resembles his original 1950s appearance, and much to Wheeler’s daughter Judy’s delight the moustache is gone.

Tex isn’t the state’s “biggest Texan” any more … he is outsized by the Sam Houston statue in Huntsville, but this lanky character holds a special place in generations of Panhandle residents’ hearts and tourists’ photos.

If you plan to go by and say “Howdy” to Tex, swing into 1400 North 3rdAvenue, Canyon, Texas.

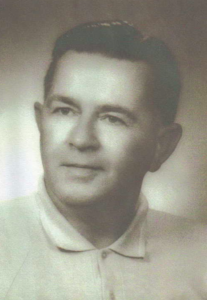

A Hero on Route 66

My last blog post about the stories behind the deserted buildings in the ghost town of Glenrio was about a dark occurrence in the local history. But these same buildings witnessed happy times, laughter, friendship and, occasionally, a heroic act.

Thirty-eight year old bus driver John David Hearon braved a blizzard on foot for 8 hours to save his passengers, and his struggle came to an end in Glenrio.

Thirty-eight year old bus driver John David Hearon braved a blizzard on foot for 8 hours to save his passengers, and his struggle came to an end in Glenrio.

At nine in the morning on a Saturday in February 1956, Hearon was driving 15 passengers from Amarillo westward in his Continental Trailways bus. Even though he was only driving 25 mph in the driving snow, the bus became stalled in a snowdrift between Adrian and Glenrio.

Because radios weren’t required on public buses at the time, (and obviously it was long before mobile phones) there was no way to call for help. There was half a tank of gas left to keep the engine running for heat, so Hearon decided to wait for assistance to arrive since the passengers were remaining calm.

The snow was soon piled waist deep.

Fuel began to run low about 2:30 p.m. and no search party had arrived. There was no food or water on the bus, and some of the passengers hadn’t eaten before leaving Amarillo (luckily, Hearon had).

He made the decision to go for help telling his passengers to stay together on the bus, and which way he was headed. Though he felt the Adrian might actually be closer, he headed west toward Glenrio to avoid walking uphill and into the wind.

The driver was only wearing his bus line uniform of trousers, a jacket, a cap, gloves and low shoes. As he began walking the snow quickly packed into his shoes and caked his pant legs before freezing into heavy ice. He later commented that though it made it more difficult to walk, the ice probably kept his legs from freezing.

He raised his jacket to cover his mount and nose for protection.

While it was still daylight he came across several stalled cars, three with people inside. He stopped to get warm in one before returning to his search.

After dark he could only tell if he had wandered off the road by the depth of the snow, and had to struggle to get back on it.

Hearon struggled on foot through the blizzard for eight hours and ten miles. When he would fall, he forced himself up knowing that his passengers were depending on him. He had lost all sense of time by the time he reached Glenrio, totally exhausted and suffering from frostbite.

The blowing snow hurt his eyes and he lost all sight in his right eye by the time he reached Glenrio. He could barely see out of his left eye, only being able to see the glare of light coming from Joe Brownlee’s gas station (the same station mentioned in my two previous posts).

He fell, exhausted, 1,000 feet before reaching the station, too weak to call out for help. He started whistling, which drew the attention of the men inside who hurried in to help him inside. They warmed him up and as soon as the ambulance arrived set out to find the bus.

Brownlee was the first to arrive at the bus in his power wagon, and brought supplies for the passengers, who had been without food for half a day. The two sandwiches that were on board during their wait had been given to 21-month old Patricia Henderson, daughter of Ruth Henderson of Rayville, Iowa.

State police followed snowplows to reach the bus next, and rescued the passengers soon afterward. The bus was pulled from the snow with heavy equipment and driven to Glenrio, where the passengers were cared for and fed. By the time the passengers were rescued they had been stranded for 23 hours, but none required hospitalization.

State police followed snowplows to reach the bus next, and rescued the passengers soon afterward. The bus was pulled from the snow with heavy equipment and driven to Glenrio, where the passengers were cared for and fed. By the time the passengers were rescued they had been stranded for 23 hours, but none required hospitalization.

They were driven to another bus in Albuquerque to continue their trip without ever having the chance to thank the brave man who risked his life to save theirs.

His doctors said that if he had ever stopped moving that it was likely he would have frozen to death.

While he recuperated in the hospital, his eyes covered in bandages, he recounted the experience to visiting journalists. He received cards and letters from all over the country.

Continental Trailways offered Hearon two extra weeks with pay, and the Treasure Island Chamber of Commerce in Florida provided he and his wife with a free vacation when he recovered.

After all this time, its unlikely that anyone seeing Brownlee’s abandoned station now remembers the story of the heroic bus driver who suffered through waist high snowdrifts to help his stranded customers.

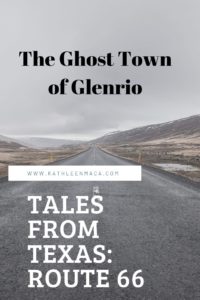

Glenrio Ghost Town: Exit 0 on Route 66

After spending the night in Tucumcari, New Mexico so we could get a “running start” at the stretch of Route 66 that cuts through Texas, we headed out to find our first bit of nostalgia.

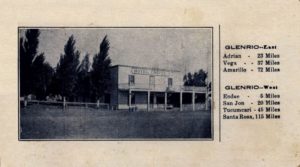

Glenrio is a town that’s actually in two states, straddling the border of New Mexico and Texas, so it was an ideal place to begin our adventure. Now a ghost town (although it still technically has two residents), it sits silently except for the hum of semis rushing down Interstate 40 just about 1000 feet behind what was once a popular stop along Route 66.

Crossing into the Lone Star State and Central Time zone, we took Exit 0 and two short right turns to end up on the original roadbed of old Route 66 that runs through town.

My heart raced a bit, because the crumbling bones of the few remaining buildings looked so familiar to me after doing much research for the trip. That’s when it hit me that we were actually doing this roadtrip I’ve looked forward to for so long!

Here’s just a bit of background on the town to put things in perspective (then we’ll get to the ‘good stuff!’).

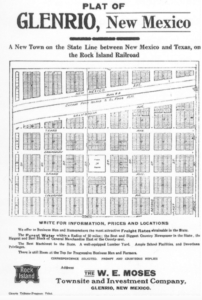

The town site was primarily populated by large cattle ranches, and then wheat and sorghum farms. Chicago, Rock Island and Gulf Railway established a station there in 1906, one year after the region was opened to small farmers to settle.

In September 1910, J. W. Kirkpatrick opened the first business in town, the Hotel Kirkpatrick. Other buildings soon popped up including grocery an d mercantile stores, a bakery, a post office, the Glenrio Tribune newspaper (published from 1910-1934), a barber shop, a blacksmith shop, a feed store, a telephone exchange and a Methodist church. A school was added to the community in 1912.

d mercantile stores, a bakery, a post office, the Glenrio Tribune newspaper (published from 1910-1934), a barber shop, a blacksmith shop, a feed store, a telephone exchange and a Methodist church. A school was added to the community in 1912.

In the 1920s the government improved the dirt road running through town by paving it and dubbing it as part of the Ozark Trails Highway. By then the town had added a hardware store, a land office, more hotels/motels, service stations and cafes.

In the 1920s the government improved the dirt road running through town by paving it and dubbing it as part of the Ozark Trails Highway. By then the town had added a hardware store, a land office, more hotels/motels, service stations and cafes.

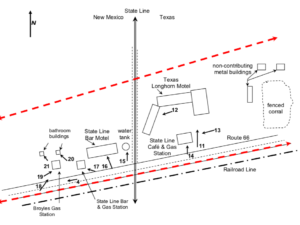

One of the amusing facts about Glenrio is how its businesses were divided by the states they sat in. Deaf Smith County in Texas was dry, so the bars and any establishment selling alcohol were built on the New Mexico side of town. No service stations were on the New Mexico side because of that state’s higher gasoline tax. Just a few steps along the road changed the laws and the prices.

The original Glenrio post office was on the New Mexico side, even though the mail arrived at the railroad depot on the Texas side. Years later a new post office was built on the Texas side.

In 1940, just two years after the final pavement through the Llano Estacado terrain of Route 66 was finished, scenes for the movie version of John Steinbeck’s The Grapes of Wrath was filmed in Glenrio for three weeks. Pretty big excitement for a little panhandle town.

At the midpoint between Amarillo and Tucumcari, Glenrio became a popular stopping point for Route 66 travelers and a “welcome station” was built near the state line.

The town’s population never rose above about 30 people. Most of the residents made their living from tourist based operations for Route 66 in the 1950s, but its popularity couldn’t save the town when Interstate 40 was built, bypassing the community.

The Rock Island Railroad depot closed in 1955. By 1985 the Texas post office was the only business open, but it has now long been closed.

You’ll want to step carefully if you walk off the road toward the buildings, because the biggest population in this town just might be the snakes judging by the number of holes I saw in the dirt.

The remnants of the few buildings left standing each must have innumerable stories to tell, if only they were able. All of the remaining buildings are on the north side of the road.

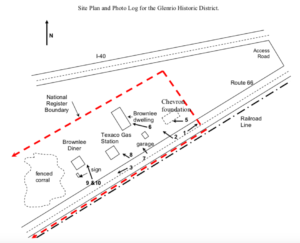

Texaco Gas Station and Brownlee House

One of the first things visitors encounter is this old, abandoned Pontiac in front of a forlorn gas station. Thanks to the fascination for abandoned places and the internet, even those who haven’t visited Glenrio are familiar with the car. What most dod’t realize is that the classic automobile has a much darker story than most cars that are left in place to rust, but I’ll share that in my next blog post. (You can find the story here.)

Built by Joe Brownlee in 1950, this Texaco station still sports its original gas pumps and front door, which is pretty amazing considering the harsh climate and years of abandonment. Because it was posted as private property and was in such close proximity to the Brownlee House, I respected the owners privacy by not venturing too close. But I sure WANTED to!

Joseph (Joe) Brownlee House

Sitting about 40 feet in back of the station is the Joe Brownlee house. Originally built in Amarillo ca.1930, he moved the bungalow style home to this location in 1950 to inlaced wrought iron porch posts and a faux stone veneer.

Roxann Travis, daughter of Joe Brownlee still resides in the home, and if you hear dogs barking when you step out of your care…they’re hers. It’s pretty fascinating to think of her living her entire life in Glenrio.

An interview once quoted Roxann as relating that, “My father had two gas stations here. Traffic would be lined up both directions. He’d have all five of us kids out there washing windshields and changing the oil so all they had to do was pump gas and keep moving them through as fast as we could.”

“We used to keep horses across the road but it was hard to get to them there were so many cars. When my kids were being raised here, they played ball on the road. You could take a nap on it now.”

West of the house is a picturesque horse corral made of native wood, and a handful of agricultural buildings.

Brownlee Diner / Little Juarez Cafe

This little Streamline Moderne building sits just west of the Texaco gas station. It housed the Brownlee Diner, later known as the Little Juarez Café. It served its last meal in 1973.

The curved aluminum sign panel on the roof has the barely discernible word “Diner” visible on each side. On the east side I could barely make out the outline of a Mexican sombrero with the words “Little Juarez.” Photos that I’ve seen of the diner from as few as five years ago show the lettering quite a bit more clearly. Panhandle weather is a tough beast.

The windows were covered from the inside (no peeking allowed, evidently!), so there was no sense in disobeying the ‘No Trespassing’ signs posted all over the property.

But the little building does have quite a modern day claim to fame…

Does this look familiar from the movie “Cars?” Yep, it was the inspiration! The animators for the movie actually traveled Route 66 and used many of the roads iconic sites in the film.

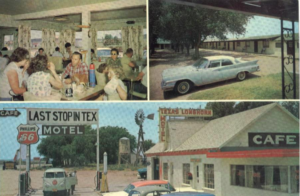

Texas Longhorn Motel, and the State Line Cafe & Gas Station

In 1939, businessman Homer Ehresman purchased the State Line Bar and operated it for several years before selling the property to Joseph Brownlee. In 1953 Ehresman constructed the State Line Café and Gas Station just east of his former property on Route 66.

The one story building housed both the cafe and gas station, and a garage bay for auto repairs was on the west end of the structure. Not surprisingly, none of the twenty-light glass panels in the original bay doors are intact. An original hydraulic auto jack sits inside.

In 1955 the Ehresman family opened the Texas Longhorn Motel directly in back of their gas station and cafe, which was in operation until 1976. The U-shaped motel featured side eaves supported by wrought iron posts to provide guests shade on the walkways in front of the rooms.

As I walked into the center court of the motel (it was difficult to imagine it filled with autos at one time), I could easily see that the “U” was composed of two sections.

The wing to my  left (on the west) housed five rooms of stucco construction, and had most of its original doors. I was surprised to find that each of the rooms once had small kitchens in addition to a sitting area, bed area and bathroom. Though some of what must have been original furnishings were inside, they were covered with crumbled drywall from the ceilings and walls.

left (on the west) housed five rooms of stucco construction, and had most of its original doors. I was surprised to find that each of the rooms once had small kitchens in addition to a sitting area, bed area and bathroom. Though some of what must have been original furnishings were inside, they were covered with crumbled drywall from the ceilings and walls.

The eight rooms at the back (north side) of the court appeared to be more simple, with a bedroom, bath (much of the original tile in place) and closet constructed on concrete block.

A detached office wing to the right (east) also providing living space for a manager, and was apparently occupied once again as recently as five years ago. Even then the condition of the building would have been rough, to say the least. Whoever lived there seems to have left their furnishings (or those provided to them) behind.

The most recognizable feature of the property to Route 66 afficiandanos is what is referred to as the towering “First-Last Sign” built directly in front of the buildings in 1955. Considered one of the most popular novelties along Route 66, it originally read “Motel – First in Texas – Cafe” or “Motel – Last in Texas – Cafe” depending on which was motorists were driving. A line of cars waiting for the pumps was a daily sight during the Route’s heyday. Now the only cars in in sight are ones that haven’t run for years, and the famous sign sits deteriorating. Soon none of the words will be left.

State Line Bar & Motel

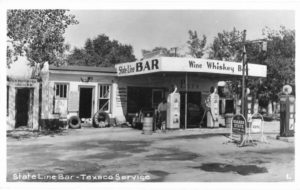

The State Line Bar and Texaco gas station (gee, all the “necessities” in one stop!) was built about 1935 by John Wesley Ferguson who originally came to Glenrio to be the Rock Island station master. It was remodeled in 1960 with a concrete block exterior and aluminum and glass door. The little wooden lean-to building in the left of the old photo above (taken ca. 1950) functioned as the New Mexico post office.

Peering inside you’ll glimpse the caved-in ceiling, and pieces of carpeting and wood paneling. Other than that and some refuse there isn’t much to see.

To the northwest of the bar is an abandoned eight-unit adobe motel built ca. 1930. The main façade has nine entrances, with eight opening to guest rooms and one to a storage area. A concrete sidewalk runs across the front of the motel in front of the warped, three-panel doors and each room has a window whose glass has long since disappeared.

To walk far enough back on the lot to reach the rooms, you’ll want to be wearing boots or snake guards because . . . well, yeah. The nearest hospital isn’t exactly around the corner.

Ferguson (Mobil Oil) Gas Station & Post Office

This charming little concrete block and stuccoed wood ruin was originally a Mobil gas station built in 1946 by John Wayne Ferguson, Jr. Its missing all of its doors and windows, which makes it appear even older than it is. The wood ceiling has collapsed into a maze of slats for the sun to filter through, creating patterns on the debris inside.

My favorite part of this building is the ghost sign reading “Post Office” on one side. It was a fun discovery when I was walking among the remnants of buildings trying to identify them. For this one I only needed to literally read the writing on the wall!

Texas Route 66 Roadbed

One sight that many visitors to Glenrio may not even realize they are looking at is a section of the original Route 66 roadbed that runs through town.

The first road through Glenrio was a dirt track which was gradually improved in the 1920s as part of the Ozark Trails highway. In 1926, the section of road was officially designated as U.S. 66, with a two-lane paved road completed through Glenrio by the late 1920s. Due to the popularity of the town and amount of traffic on the road, Route 66 was widened to four-lanes with a concrete median added on the New Mexico side. This asphalt-surfaced, four- lane highway remains drivable, but eventually runs into dirt road where the state pulled up the asphalt to avoid maintenance.

Grass now grows through the cracks in the asphalt on the four lanes but its worth the short drive just to say you’ve traveled part of the original Route.

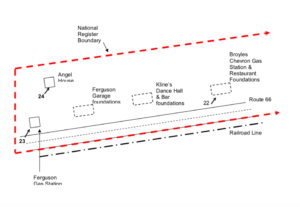

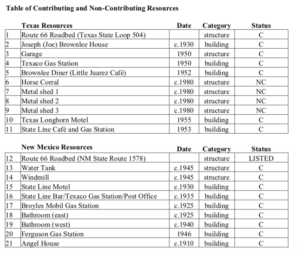

A handful of other foundations exist, but I won’t mention them here since the buildings they supported are gone. If you explore the town in person or just via Google maps, this key to the buildings and foundations will help to act as a good guide.

A handful of other foundations exist, but I won’t mention them here since the buildings they supported are gone. If you explore the town in person or just via Google maps, this key to the buildings and foundations will help to act as a good guide.

You can drive through Glenrio in less than one minute without even going the speed limit, since the drive is just over a mile in length, but there is so much history there for those willing to stop.

After a bit of exploring, it was time to hop back in the car (and air conditioning), drink some cold water and to head to our next stop which I’ll share soon!

Getting Our Kicks on Route 66

Not every good trip takes a lot of planning, but it really pays off when you’re going on a “theme” trip with family members!

This summer’s goal was to drive the section of Route 66 that goes through the Texas Panhandle, and I definitely did weeks of research through travel bureaus, internet, books and maps. I enjoyed the process and it really built up the anticipation for me!

After doing a preliminary review of the sites along the way, I decided to spread the drive across six days. Now, If you’re familiar at all with this section of Route 66 or the Panhandle, you’re probably thinking I may have lost my marbles since this stretch of road is just under 200 miles long and would only take about three hours to drive straight through!

But stay with me, here! There was so much to see!

I decided to actually begin the drive in Tucumcari, New Mexico which is only about an hour west of the Texas border. I fell in love with photos of the old, restored motels from Route 66 that are still operating here while I was doing my research. It also helped to make sure we were going to include every inch of the Texas section of the road, which I was determined to do!

The route would take us across the Panhandle to Texola, Oklahoma (although we took it all the way to Oklahoma City so we could cut south and spend a few days with friends on their ranch).

One of the challenges of planning the trip was to incorporate things that would be of special interest to everyone in my family.

My 17-year-old daughter is interested in music, animals, and antique and thrift shops. First things, first…she was in charge of the playlists for the road trip, and I’m so glad she was! She enjoys “vintage” music (like, um, from when I was in high school) as well as some of the new and alternative bands. My husband and I got to enjoy old favorites and hear some terrific new music and only once (yes, once!) asked her to skip to the next song.

We came across plenty of animals on the trip, which was a treat, but incorporated riding horses into our “definitely do this” list. Seeing the land from horseback always seems to make exploring the outdoors more special.

There were countless antique and resale shops along the way, so I dove in and checked out online photos and reviews to find some that might suit her particular interests.

Special bonus: she recently got her driver’s license so she helped with the driving, too!

My husband is a ham radio operator (AB5SS, if any of you are, too!). He has a “roving” antennae and is operating to contact every “grid” in the United States. He decided to use this opportunity to help other “hams” contact grids along Route 66 that are difficult or impossible

to cross off their wishlists…and he sure made some people happy! He has a map of where each grid is along the way, so we made a point to stop (at least once) in each grid to give him a chance to operate. He announced via his twitter account that he would be doing this so that interested hams could mark it on their calendar, and then announced prior to each broadcast where they could find him on the air. He made over 150 contacts during the trip! That’s a lot of happy ham operators.