A small, unassuming grave marker stands in the Trinity Episcopal Cemetery of Galveston, located at Forty-First Street and Broadway. Tough simple in design, it marks a New Year’s Day that encompassed the tragedy of the War Between the States; the day a Confederate officer embraced a dying Union officer, his own son.

When West Point graduate and military veteran Colonel Albert M. Lea moved to Texas in 1857 his son Edward remained in Maryland to attend the United States Naval Academy and continue the celebrated military tradition of the family; the same family that would be devastated by fighting each other within the very country they loved.

As a Texan and friend of General Sam Houston, Albert Lea applied for a Confederate commission in March 1861, just one month before the Civil War began. He wrote a letter to his then 26-year-old son advising him to follow his conscience when he made the decision regarding which side of the conflict to support, but added an ominous warning: “If you decide to fight for the Old Flag,” he said, “It is not likely that we will meet again, except face to face on the battlefield.”

Edward chose loyalty to the Union, telling his fellow officers he did not desire his family’s love if it involved being a traitor to his country.

After months of serving in a variety of locations, Colonel Lea was transferred back to Texas on December 15, 1862, staying with his wife and family at a relative’s home in Corsicana.

Once in the area, Lea learned that the Union vessel Harriet Lane on which he believed his son was serving, had been occupying the harbor of Galveston since the Union captured and occupied the island earlier in October. Lea hurried to Houston to long-time friend General Magruder’s headquarters, where he learned that a plan to recapture Galveston Island would be executed within a week.

During the pre-dawn hours of January 1, 1863, Lea helped to move six brass cannons of Captain M. McMahon’s battery across Galveston Island’s rail causeway. Afterward, Colonel Forshey posted Colonel Lea in one of the town’s tallest buildings near Broadway (some reports suggest a church, others Ashton villa) to observe and report the status of the attack.

A severe battle ensued, during which the Westfield, which had run aground off Pelican Spit, was blown up, and the Confederate gunboat Bayou City rammed the Harriet Lane near the wheelhouse, which allowed the Confederate troops to overrun the vessel. The remainder of the Union fleet fled to New Orleans, leaving three companies of the 42nd Massachusetts infantry on Kuhn’s Wharf to surrender. The rebels had retaken the city at a cost that was yet to be seen.

Colonel Lea rushed to Kuhn’s Wharf waterfront near where the battle had taken place. Once granted permission to board the Harriet Lane, he learned that her Union commander, Captain Wainwright, was dead and Lieutenant Commander Edward Lea, the executive officer, had been shot through the stomach.

Making his way through the soldiers pillaging the ship, Lea found his son lying in the cockpit, surrounded by dead and dying comrades.

Dr. Penrose, who was operating on a wounded man, handed Colonel Lea a flask of brandy for his son to sip, telling the grief-stricken father that the wound was mortal.

Cradling the young officer’s head, Colonel Lea said, “Edward, this is your father.”

“Yes father, I know you,” the young man whispered in return, “but I cannot move.”

In a desperate attempt to change fate, the Colonel went ashore to arrange for his son to be moved to the Sisters of Charity Hospital. After relating the events to General Magruder, whom he met along the way, Magruder offered his private quarters for his friend’s son.

While his father was absent, the lieutenant was told that his death was near and was asked if he had any last wishes. With his last breath, Edward replied, “No, my father is here.”

When Albert Lea returned, his brave son was dead. The next day an elaborate funeral procession that included Confederate and Union officers, sympathetic local citizens, a drum corps of prisoners from the battle and a group of Masons in full regalia solemnly carried

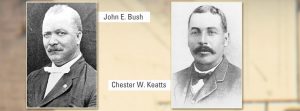

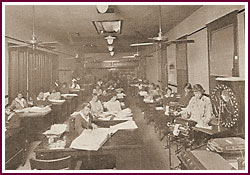

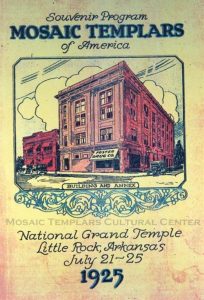

de a newspaper, hospital, and building and loan association. The organization attracted thousands of members and built a complex of three buildings at the corner of West Ninth Street and Broadway in Little Rock, Arkansas. The National Grand Temple, the Annex, and the State Temple were completed in 1913, 1918 and 1921, respectively.

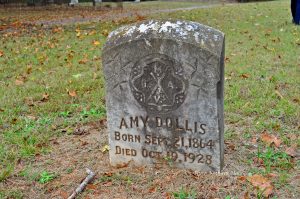

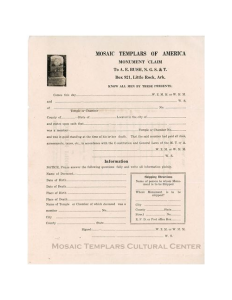

de a newspaper, hospital, and building and loan association. The organization attracted thousands of members and built a complex of three buildings at the corner of West Ninth Street and Broadway in Little Rock, Arkansas. The National Grand Temple, the Annex, and the State Temple were completed in 1913, 1918 and 1921, respectively. sed MTA member to receive an MTA marker, local chapter officers had to complete and sign the monument claim form to verify that the deceased MTA member had paid all dues and fees, and confirm that the deceased was a member in good standing. They also had to submit the member’s information that was to be placed on the marker, and had to provide a delivery address for the completed marker.

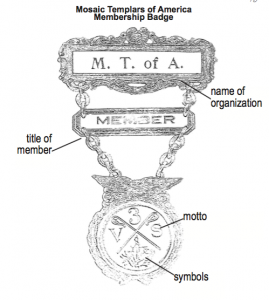

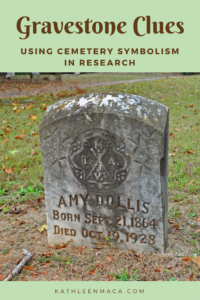

sed MTA member to receive an MTA marker, local chapter officers had to complete and sign the monument claim form to verify that the deceased MTA member had paid all dues and fees, and confirm that the deceased was a member in good standing. They also had to submit the member’s information that was to be placed on the marker, and had to provide a delivery address for the completed marker. he Mosaic Templars. The letters “M,” “T” and “A” denote the

he Mosaic Templars. The letters “M,” “T” and “A” denote the  s and Aaron and Exodus story from the Bible. The “3v’s” abbreviates the Latin phrase “Veni Vidi Vici,” meaning “I cam

s and Aaron and Exodus story from the Bible. The “3v’s” abbreviates the Latin phrase “Veni Vidi Vici,” meaning “I cam f the decade it had ceased operations in Arkansas.

f the decade it had ceased operations in Arkansas. When you’re in Little Rock, visit the Mosaic Templars Cultural Center museum at 501 West Ninth Street downtown.

When you’re in Little Rock, visit the Mosaic Templars Cultural Center museum at 501 West Ninth Street downtown.

just a teenager, Judy Bell Tally married Jessie Burse. The couple lived on a farm in Gilmer, in Upshur County, Texas and had a daughter named Estelle in 1913.

just a teenager, Judy Bell Tally married Jessie Burse. The couple lived on a farm in Gilmer, in Upshur County, Texas and had a daughter named Estelle in 1913.

Having escaped from an abusive marriage to an alcoholic husband, Elizabeth Percival started a new life with her two step-daughters Florence and Jessie. She opened a restaurant named The English Kitchen, serving the English dishes from her childhood with a boarding house on the floors above it. In the following months she and the girls gained a loyal following of customers and friends.

Having escaped from an abusive marriage to an alcoholic husband, Elizabeth Percival started a new life with her two step-daughters Florence and Jessie. She opened a restaurant named The English Kitchen, serving the English dishes from her childhood with a boarding house on the floors above it. In the following months she and the girls gained a loyal following of customers and friends.