Tag: wildflower

Bon Jour, Professor!

I’ve walked through the seven cemeteries on Broadway in Galveston countless times, photographing, doing research, assisting in restoration, and simply enjoying the history. So I was very surprised this week to find a grave marker that I haven’t taken notice of before.

May is my favorite time to take photos there, because the city allows the coreopsis of spring to overtake the cemetery for the month. No one can resist veering off the main avenue to enjoy a closer look

May is my favorite time to take photos there, because the city allows the coreopsis of spring to overtake the cemetery for the month. No one can resist veering off the main avenue to enjoy a closer look at the exquisite sight.

at the exquisite sight.

Wandering down one of the sidewalks to get some close-ups, a stone that was obviously facing the “wrong direction” caught my eye and I walked around the other side to investigate.

Imagine my delight to see “Professor” J. B. Maton as the name, and that he was born in the 18th century. Now, there simply HAD to be a story there! I hadn’t ever heard his name before, but I was determined to investigate once I got home.

The first evidence I have found of John B. Maton living in Galveston was the 1850 Census. In it, he is listed as a 56-year-old schoolteacher who was born in France. Living with him was a 19-year-old male named Martin Maton, who we can presume was his son.

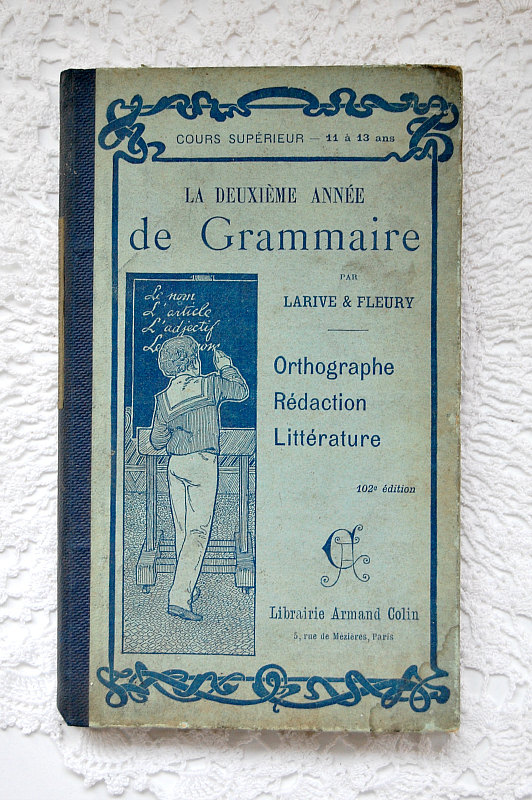

By the fall of 1851, Maton was running advertisements in the local newspapers for his “Male and Female Academy,” stating that he had lived all of his life in the principal cities of France, England and Germany and devoted the last 27 years to teaching.

The professor conducted the academy from his house on Twenty-fourth street, one door south of Church Street opposite the Tremont garden. It contained two classrooms “besides every other convenience for an institute as also a large garden with fine shrubbery and a good cistern.”

The professor conducted the academy from his house on Twenty-fourth street, one door south of Church Street opposite the Tremont garden. It contained two classrooms “besides every other convenience for an institute as also a large garden with fine shrubbery and a good cistern.”

Mason also taught for a period of four years in Liberty county, between 1852 and 1856.

He signed his name as “Prof. T. Maton” so he presumably went by his middle name, but I could not find any record of what that was.

For two seasons of five months each beginning in September, students could attend the academy for $3 per month ($30 per year) for seniors (older students) or $2 per month ($20 per year) for juniors (younger students), requiring all fees to be prepaid. Compared to today’s private school, this seems like quite a bargain!

School ho urs were from nine in the morning until four in the afternoon. Subjects included English, French and German languages, history, geography, astronomy, and arithmetic, each taught in “an agreeable style.”

urs were from nine in the morning until four in the afternoon. Subjects included English, French and German languages, history, geography, astronomy, and arithmetic, each taught in “an agreeable style.”

His ads also always emphasized that “particular attention will be paid to impress the pupils with good morals and fine manners.”

“Miss Maton will take charge of the female department.” This could have been Maton’s sister, or daughter. I have not been able to find any mention elsewhere of a female Maton living in the city, much less the household. If anyone has any information about her, I would love to hear about it.

Prospective families could register their students either directly with Professor Maton, or at William Armstrong & Brothers Great Southern Bookstore and Stationers on Tremont. (For more about Civil War veteran William Armstrong, see “Galveston’s Broadway Cemeteries,” available on Amazon.com)

With the advent of war, John Maton enlisted in the Confederate 11th Battalion of Texas Volunteers in Company F with a rank of private. This unit of cavalry and infantry were under the direction of Lt. Colonel Ashley W. Spaight and Major J. S. Irvine.

The professor’s death occurred just one year after enlistment, but I have been unable to find any details. It could just as likely been the result of disease as injury in battle. Either way, his body made it back to Galveston for burial in Trinity Episcopal Cemetery alongside some of the era’s most illustrious citizens.

(NOTE: There was another John Maton from Refugio County, Texas who served in the Civil War, but he survived. Keeping their records distinct from each other takes a bit of care.)

Professor Maton is just one of the stories that hides beneath the stones in historic cemeteries, waiting for someone to take the time to discover and remember them.