Tag: backroads

Walking in Their Steps: San Felipe de Austin Historic Site

Happy New Year!

So many of us start off each new year by looking back, so I thought it was only appropriate to begin 2020 by sharing a place that brings us back to the beginning of Texas: San Felipe de Austin State Historic Site.

Open since April 2018 the San Felipe de Austin Museum is simply one of the most beautifully interpreted historical sites I’ve seen, especially considering there is virtually nothing left of the original settlement. Inside, visitors can interact with touch screen displays to learn details about the settlement, and outside they can walk in the steps of settlers and explore the townsite.

Sitting on the bluff of the Brazos River on the actual site of the former colony it honors the spirit of early Texas pioneers.

San Felipe de Austin was established in 1823 by Stephen F. Austin, known as the “Father of Texas,” as a headquarters for his colony in Mexican Texas. The town had four public squares: Commerce, Constitution, Military and Campo Santo Cemetery.

The first area to visit after paying admission in the gift shop/reception area is a small viewing area for a short film that gives an overview of the history of San Felipe de Austin. Interesting and beautifully produced, it puts the history of the site and people who lived here in context as you continue through the property.

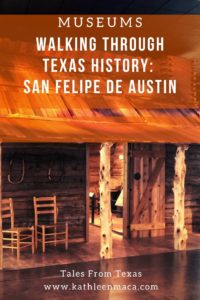

Entering the museum space, the first thing you’ll encounter is a replica of a log cabin. Displays like a spinning wheel and dress-up corner give a bit of information about pioneer life, but make sure you stand for a moment in the space and realize that this small cain would often house an entire family.

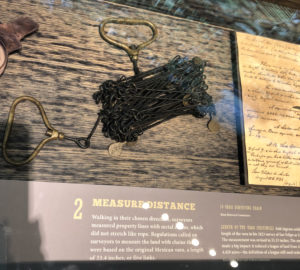

A corner across from the cabin holds a field desk that actually belonged to Stephen F. Austin, and display cases contain examples surveying equipment that would have been utilized in laying out the colony and surrounding land grants.

Other displays showcase artifacts recovered during archeological excavations that give visitors a peek into the everyday lives of early Texans.

One of my favorite things about the museum is the number of interactive displays. Adults enjoy them, of course, but as a parent and Girl Scout leader who has traveled with children of all ages, I know how these fascinating exhibits can draw people into history through high tech applications.

One of my favorite things about the museum is the number of interactive displays. Adults enjoy them, of course, but as a parent and Girl Scout leader who has traveled with children of all ages, I know how these fascinating exhibits can draw people into history through high tech applications.

Walk up to a lighted, multimedia illustration of the settlement and touch key numbers to learn more about the different buildings (offices, the school, individual homes) and people who once existed there. (And yes, you know that I touched every single one!)

Turn around and walk up to a tabletop display to learn about some of the big decisions the officials of San Felipe de Austin had to make. Once you’ve made a decision about the issue, you can cast your vote, and see the results.

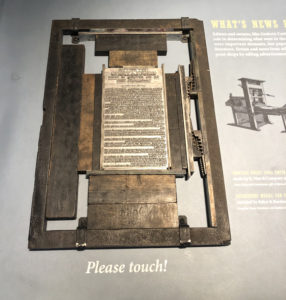

A colonial printing press like one used to print the Texas Gazette, at times renamed the Mexican Citizen, in San Felipe from 1829 to 1832 stands proudly in its own corner, along with a printing plate that . . . yes, really . . . visitors are encouraged to touch.

The display explains the vital role the press played both in the community and in the history of the state:

“The first book published in Texas, written by Stephen F. Austin, was printed by the Gazette press in 1829. In 1835, the Telegraph and Texas Register began operating under the guidance of Gail Borden, Jr. and soon became the unofficial voice of the Texas revolution movement. It also printed many other important Texas documents, including the Declaration of Independence.”

“The first book published in Texas, written by Stephen F. Austin, was printed by the Gazette press in 1829. In 1835, the Telegraph and Texas Register began operating under the guidance of Gail Borden, Jr. and soon became the unofficial voice of the Texas revolution movement. It also printed many other important Texas documents, including the Declaration of Independence.”

Impressed? I was, too.

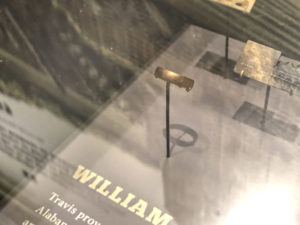

I encourage you to take your time and read the descriptions that accompany seemingly small fragments and objects in cases that line the walls. There are priceless treasures and surprises among them.

William B. Travis was a town resident before his death at the Alamo, and he sent his famous “Victory or Death” letter from the Alamo to San Felipe. A ring thought to have belonged to him was excavated from his homesite and is now on display.

After exploring inside the museum, it’s time to expand your discoveries by venturing out the side doors, and into the townsite itself.

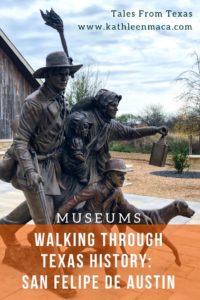

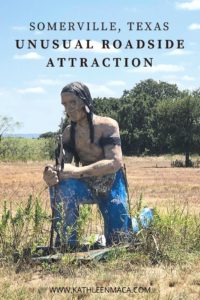

A bronze plat map sits on a platform on a covered patio, providing a frame of reference for how the settlement was laid out on the property. From here visitors can follow a mown path through the mown native grasses to visit specific sites within the former town. San Felipe was one of the most culturally diverse communities of its time in Texas. Farmers, explorers, politicians, enslaved and free people of African ancestry, intertribal delegations of local Indians, cattlemen and businessmen populated the thriving settlement.

A bronze plat map sits on a platform on a covered patio, providing a frame of reference for how the settlement was laid out on the property. From here visitors can follow a mown path through the mown native grasses to visit specific sites within the former town. San Felipe was one of the most culturally diverse communities of its time in Texas. Farmers, explorers, politicians, enslaved and free people of African ancestry, intertribal delegations of local Indians, cattlemen and businessmen populated the thriving settlement.

A tavern, bakery, stores, homestead sites and more await visitors who will quite literally be walking in the footsteps along the same paths these brave citizens did almost two centuries ago.

The Texas Revolution caused the demise of San Felipe de Austin, when the residents burned it to the ground during the evacuation known as the “Runaway Scrape” in 1836. After the fall of the Alamo, Mexican General Santa Anna and his forces briefly occupied the ruins of the town just before their defeat at the Battle of San Jacinto.

Just across the road from the museum are a few more sites you’ll want to explore. A commemorative obelisk marks the exact spot of Stephen F. Austin’s own cabin – the only home he ever owned in Texas. There is also a stoic bronze statue of the Texas hero, a replica dog trot log cabin, active excavation sites, and the original well for the colony.

.

The large white building is the J. J. Josey General Store, built on the townsite in 1847 and in continuous operation for generations before being moved here for preservation.

Visitor parking is available on site at the museum and limited parking is available across the street.

Allow yourself at least 60 to 90 minutes to enjoy the museum exhibits and the grounds, and be sure to wear comfortable walking shoes as the outside trails are unpaved and the ground is somewhat uneven.

San Felipe is just ten minutes east of Sealy, and the museum is open daily from 9 a.m. to 5 p.m. , except for Thanksgiving Day, Christmas Even, Christmas Day, New Year’s Eve and New Year’s Day.

Admission – Adults, $10; Children (5-14), Seniors, Veterans & Austin and Waller County Residents, $5, Family ticket (2 adults and 2 children) $22. For other options and to find out more about he San Felipe de Austin Historic Site, click HERE.