Skip to content

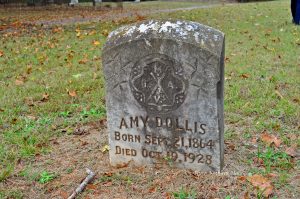

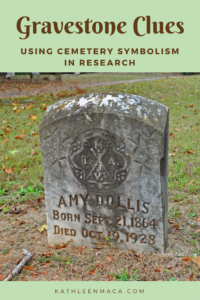

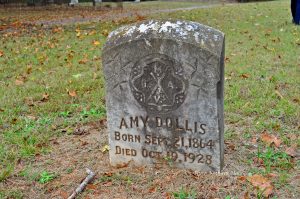

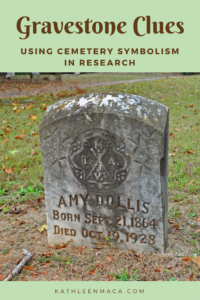

I was thrilled this weekend to find a grave marker for a member of the Mosaic Templars of America, in Marshall, Texas.

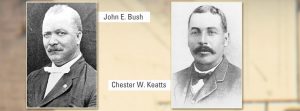

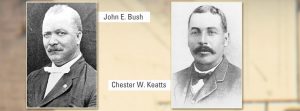

The Mosaic Templars of America was an African American fraternal organization founded in Little Rock, Arkansas in 1882 and incorporated in 1883 by two former slaves, John E. Bush and Chester W. Keatts.

The organization was established to provide important services such as burial insurance and life insurance to the African American community. Like many fraternal organizations, the Mosaic Templars’ burial insurance policies covered funeral expenses for members, both men and women, who maintained monthly dues.

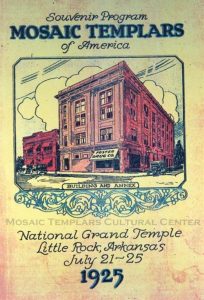

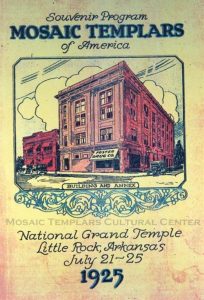

By 1913, the burial insurance policy also included a Vermont marble marker. These markers are still found in cemeteries across Arkansas and other states. As membership grew, the Mosaic Templars expanded its operations to inclu de a newspaper, hospital, and building and loan association. The organization attracted thousands of members and built a complex of three buildings at the corner of West Ninth Street and Broadway in Little Rock, Arkansas. The National Grand Temple, the Annex, and the State Temple were completed in 1913, 1918 and 1921, respectively.

de a newspaper, hospital, and building and loan association. The organization attracted thousands of members and built a complex of three buildings at the corner of West Ninth Street and Broadway in Little Rock, Arkansas. The National Grand Temple, the Annex, and the State Temple were completed in 1913, 1918 and 1921, respectively.

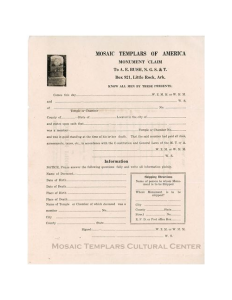

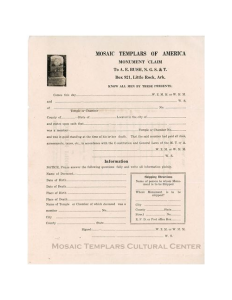

A blank Mosaic Templars of America [MTA] Monument Claim Form. In order for a decea sed MTA member to receive an MTA marker, local chapter officers had to complete and sign the monument claim form to verify that the deceased MTA member had paid all dues and fees, and confirm that the deceased was a member in good standing. They also had to submit the member’s information that was to be placed on the marker, and had to provide a delivery address for the completed marker.

sed MTA member to receive an MTA marker, local chapter officers had to complete and sign the monument claim form to verify that the deceased MTA member had paid all dues and fees, and confirm that the deceased was a member in good standing. They also had to submit the member’s information that was to be placed on the marker, and had to provide a delivery address for the completed marker.

According to their official 1924 history, the MTA authorized a Monument Department as early as 1911 to provide markers to its deceased members. Operations were managed by the state jurisdictions until 1914, when the MTA created a national Monument Department to centralize operations and cut costs. Members paid an annual tax to finance the department, and were promised a marble marker.

A traditional MTA marker had a rounded and forward-sloping top, with the MTA symbol cut into the top center. The name of the deceased member was carved below the symbol, with dates of birth (if known) and death. The name of the local chapter, the chapter number and the city where the chapter was located could be found on the bottom. MTA markers issued by the Modern Mosaic Templars of America appear exactly as the MTA markers except with the word “Modern” carved just above the MTA logo. The dimensions of the markers generally measured twenty-five to twenty-nine inches in height, fifteen to seventeen inches in width, and three to five inches in depth.

The name of the organization, taken from the Biblical figure Moses who emancipated Hebrew slaves, elected the Templars ideals of love, charity, protection, and brotherhood. The organization was originally called “The Order of Moses,” but the founders revised the name to “Mosaic Templars of America” in 1883 during the incorporation process. Modeled after the United States government, the organization consisted of an executive branch, a legislative branch, and even a judicial branch.

The organization struggled to regain its status, but by the end o f the decade it had ceased operations in Arkansas.

f the decade it had ceased operations in Arkansas.

But I want to also share a bit about Amy since it is her grave marker, after all.

She was born in Tennessee in 1864, to Abner Dollis and Celia Bloodsworth Dollis.

By the time she was 25, in 1890, she was working as a live-in cook in the home of Sheriff William Poland and his family.

Just ten years later she had married, and was the widow of, “John” whose last name was not listed in the city directory. She had a two-year -old daughter named Cely, who was obviously named for Amy’s mother.

By 1912 she supported her daughter by working as a “washerwoman,” and lived at 805 Riptoe Street in Marshall, where only a couple of older homes still stand.

Her death certificate lists her father as Abner Dollis, and her cause of death by apoplexy (the term commonly used for a stroke).

Her daughter Pearl (this was possibly a middle name for Cely), a public school teacher, married Rufus Brown. In 1910, the couple was living with Amy in her home.

Amy died of apoplexy (a term commonly used for stroke), in 1928.

Amy Dollis’ marker, the one I spotted in Marshall, is not in the database being created by the curator of the Mosaic Templars Cultural Center at this time, so I was thrilled to be able to share the find with them.

de a newspaper, hospital, and building and loan association. The organization attracted thousands of members and built a complex of three buildings at the corner of West Ninth Street and Broadway in Little Rock, Arkansas. The National Grand Temple, the Annex, and the State Temple were completed in 1913, 1918 and 1921, respectively.

de a newspaper, hospital, and building and loan association. The organization attracted thousands of members and built a complex of three buildings at the corner of West Ninth Street and Broadway in Little Rock, Arkansas. The National Grand Temple, the Annex, and the State Temple were completed in 1913, 1918 and 1921, respectively. sed MTA member to receive an MTA marker, local chapter officers had to complete and sign the monument claim form to verify that the deceased MTA member had paid all dues and fees, and confirm that the deceased was a member in good standing. They also had to submit the member’s information that was to be placed on the marker, and had to provide a delivery address for the completed marker.

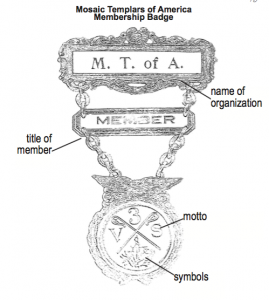

sed MTA member to receive an MTA marker, local chapter officers had to complete and sign the monument claim form to verify that the deceased MTA member had paid all dues and fees, and confirm that the deceased was a member in good standing. They also had to submit the member’s information that was to be placed on the marker, and had to provide a delivery address for the completed marker. he Mosaic Templars. The letters “M,” “T” and “A” denote the Mosaic Templars of America. The two crossed shepherd staffs in the center represent Mose

he Mosaic Templars. The letters “M,” “T” and “A” denote the Mosaic Templars of America. The two crossed shepherd staffs in the center represent Mose s and Aaron and Exodus story from the Bible. The “3v’s” abbreviates the Latin phrase “Veni Vidi Vici,” meaning “I came, I saw, I conquered.” Finally an ouroboros (snake eating its tail), representing the cyclical nature of life surrounding the symbol.

s and Aaron and Exodus story from the Bible. The “3v’s” abbreviates the Latin phrase “Veni Vidi Vici,” meaning “I came, I saw, I conquered.” Finally an ouroboros (snake eating its tail), representing the cyclical nature of life surrounding the symbol. f the decade it had ceased operations in Arkansas.

f the decade it had ceased operations in Arkansas. When you’re in Little Rock, visit the Mosaic Templars Cultural Center museum at 501 West Ninth Street downtown.

When you’re in Little Rock, visit the Mosaic Templars Cultural Center museum at 501 West Ninth Street downtown.