There are many facets to saving the history held within cemeteries; not all of them chiseled in stone.

During a cemetery workday when volunteers were busily cleaning gravestones and picking up trash, I went into one of the old buildings on site to ask a question of one of the men in charge. A new friend greeted me with a handful of crumbling papers and a horrified look on his face. “Look at this! They’re everywhere.”

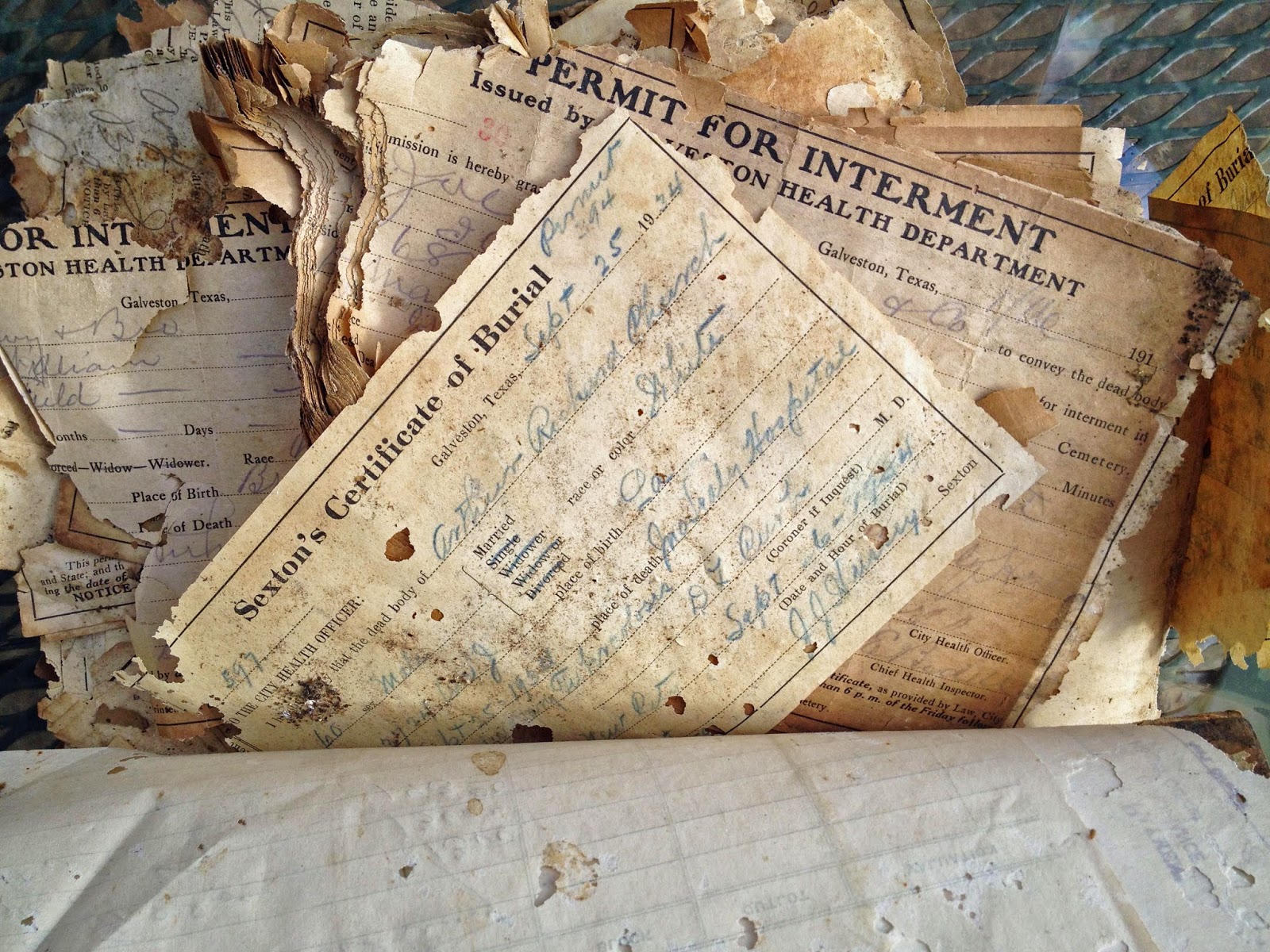

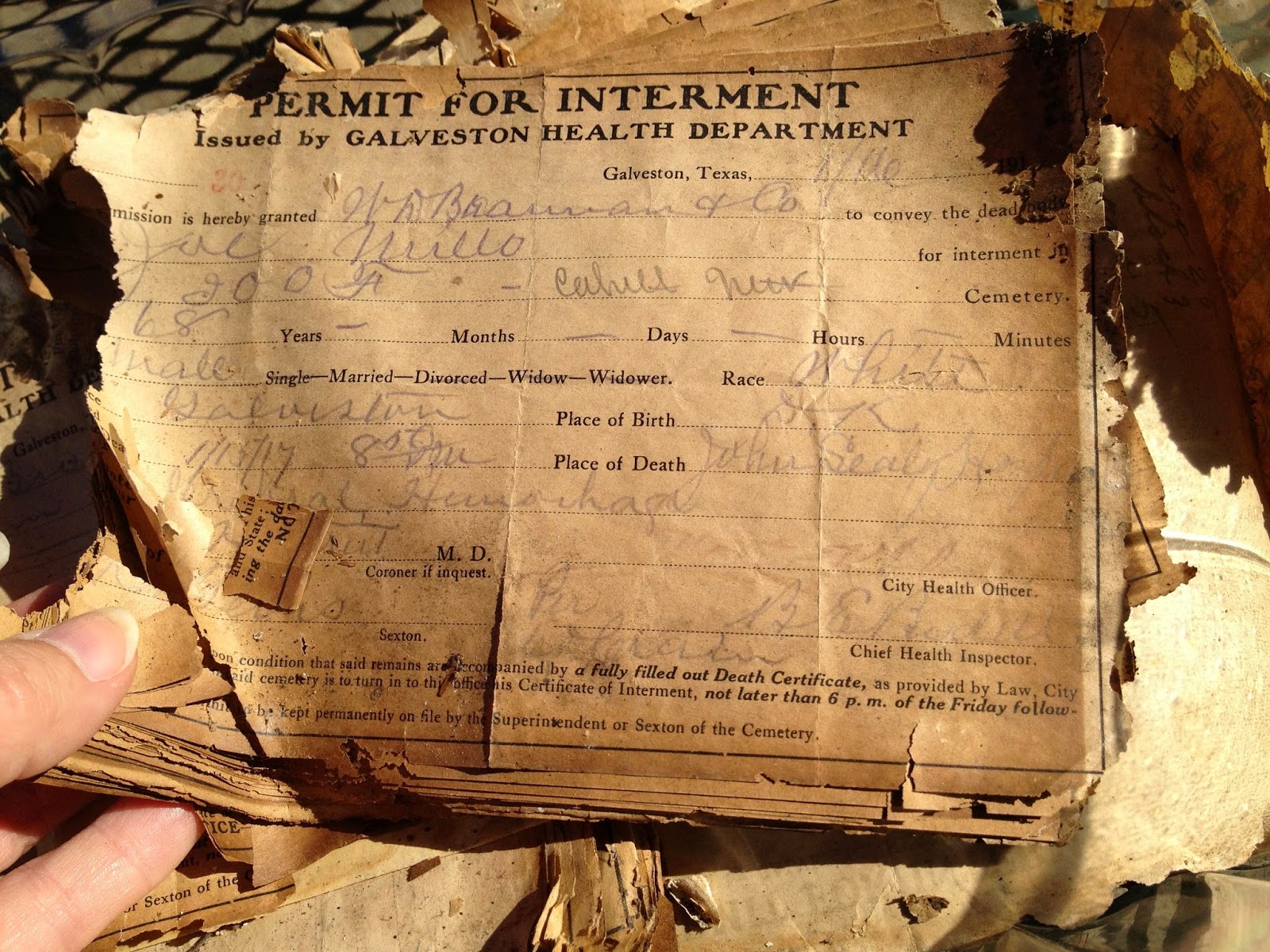

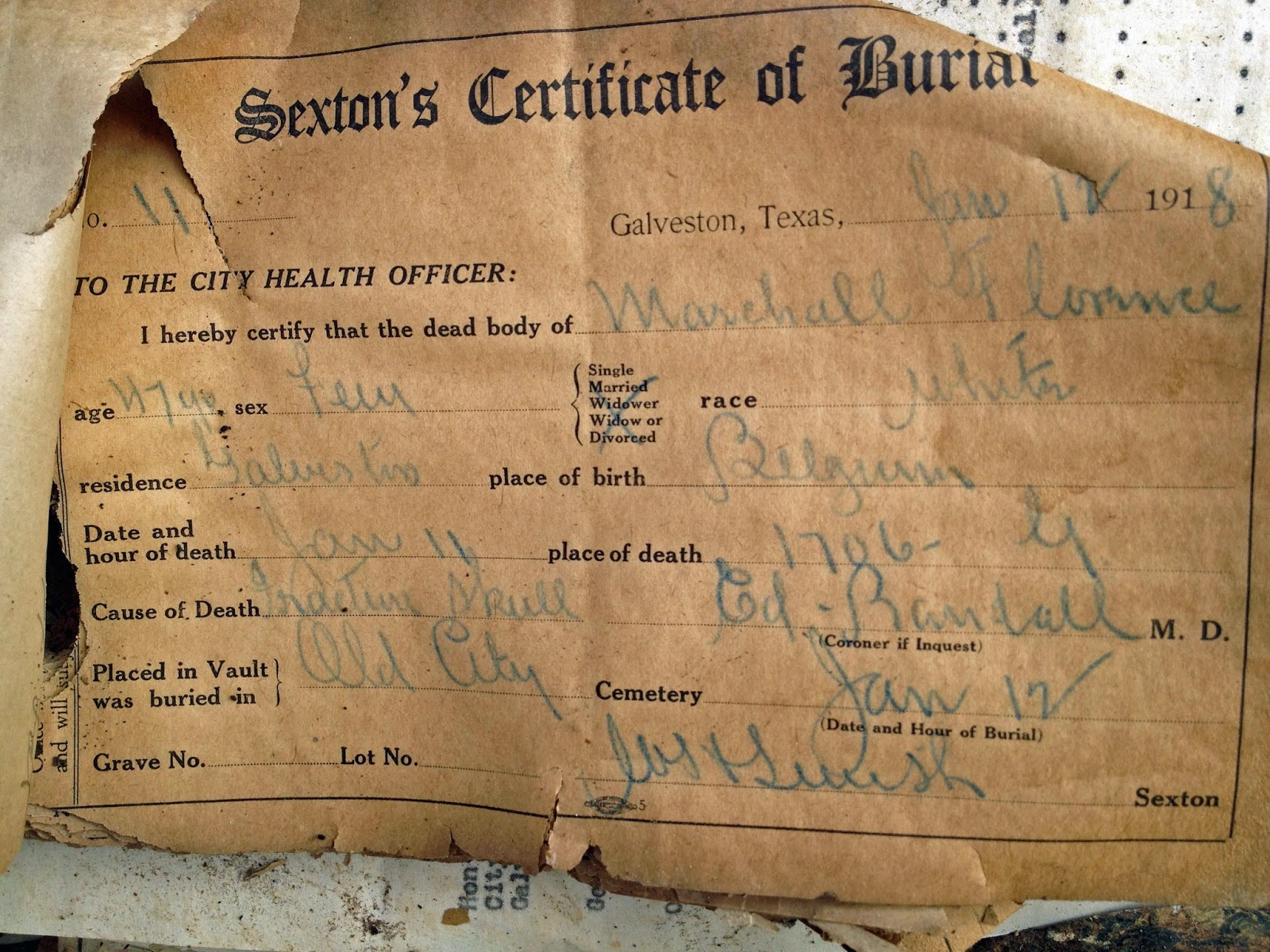

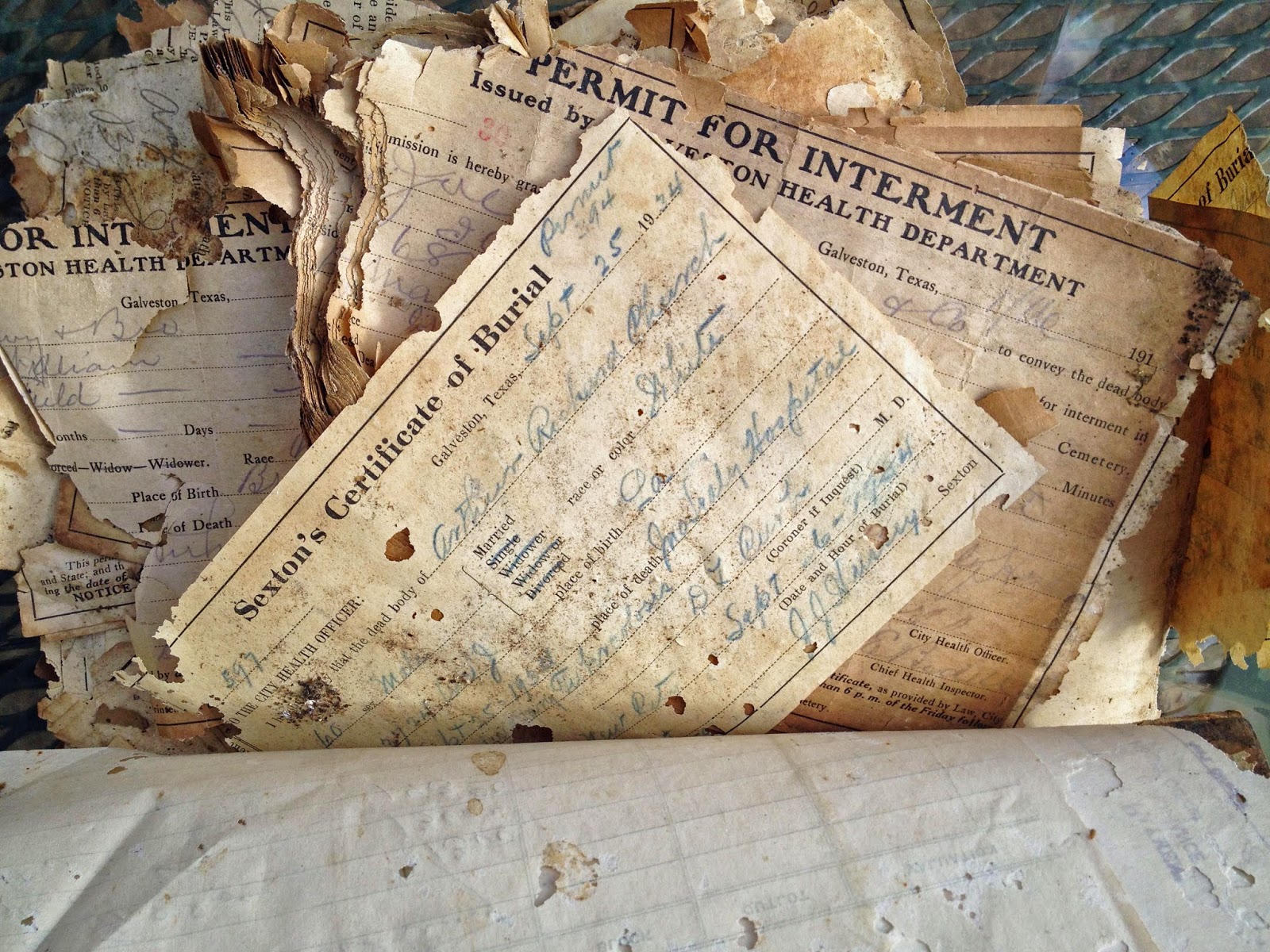

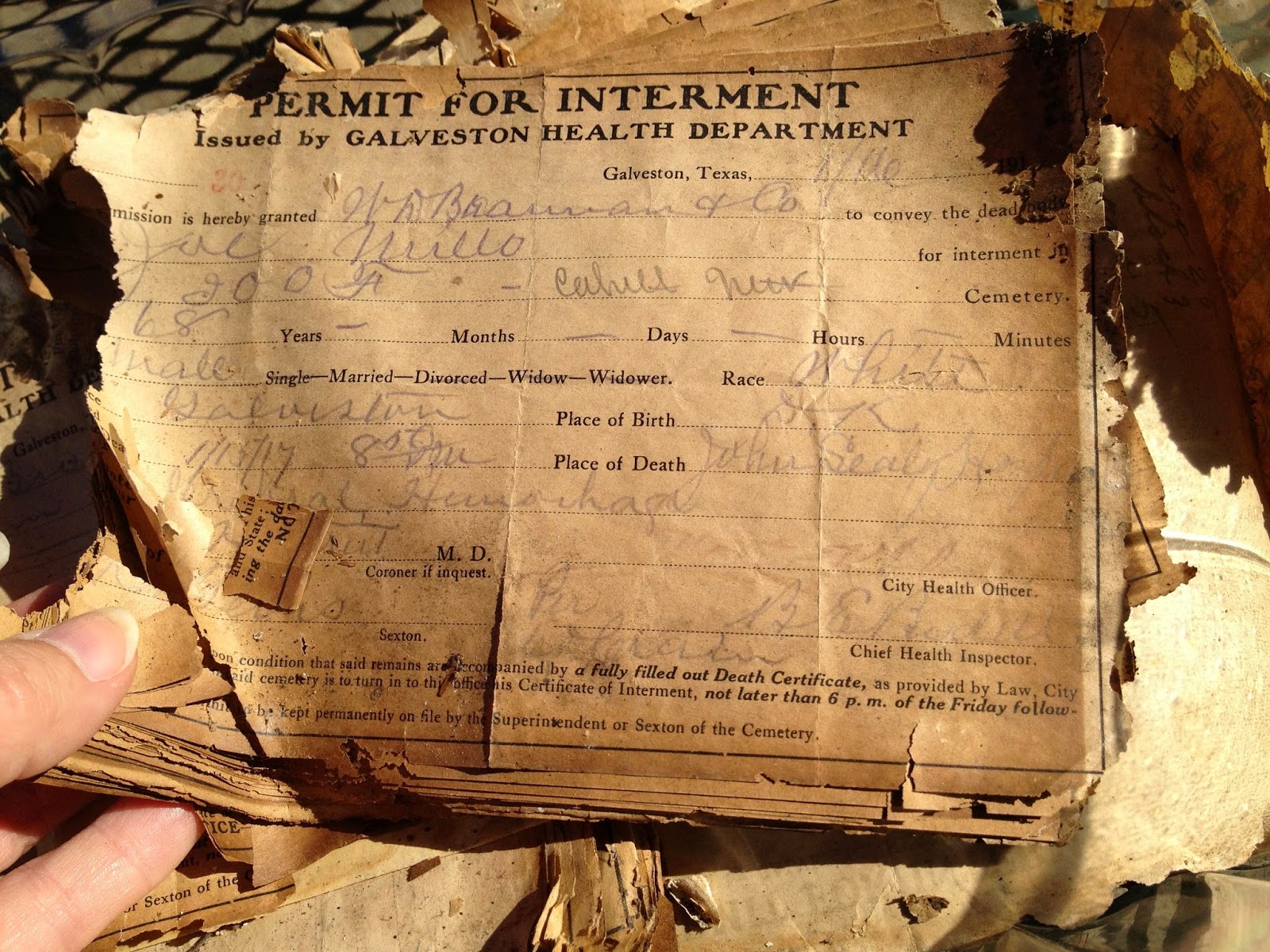

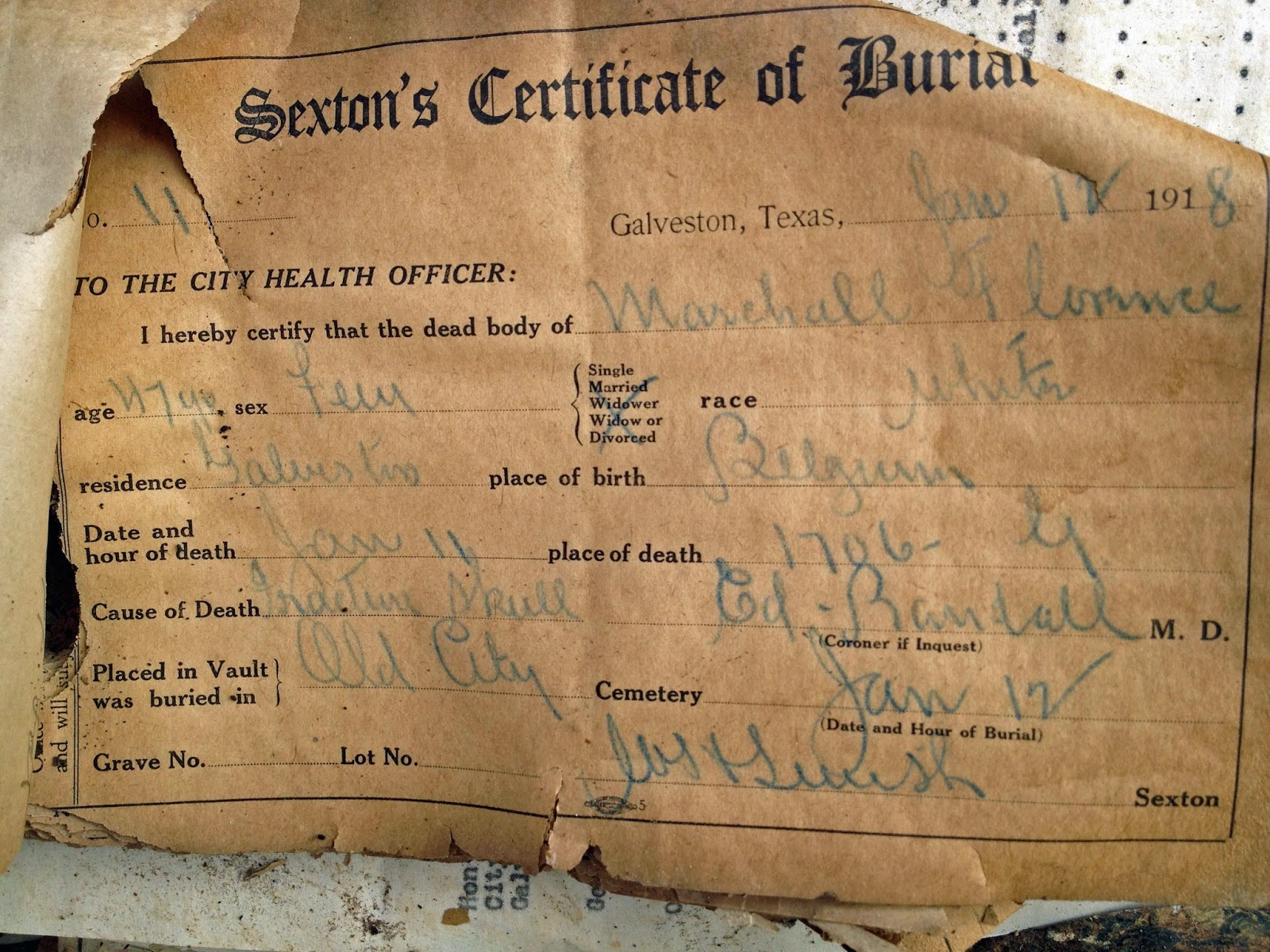

Sure enough, the original sexton records for the cemetery were scattered across the floor and heaped in a corner. Unfortunately, they had obviously been there through hurricane flood waters, insect and rodent feeding frenzies, and currently had paint cans and scrap wood laying on them. The disintegrating bits of paper had seen better days.

Most of the scraps were smaller than a fingernail with only a letter or two visible. I carefully lifted the partial and mostly full pages and stacked them for removal. The heartbreaking realization was that only a few could be retrieved. And yes, even those that I picked up were extremely fragile, and covered in feces. But they HAD to be saved!

Most of the scraps were smaller than a fingernail with only a letter or two visible. I carefully lifted the partial and mostly full pages and stacked them for removal. The heartbreaking realization was that only a few could be retrieved. And yes, even those that I picked up were extremely fragile, and covered in feces. But they HAD to be saved!

It will take quite a while, even with the little stack rescued, to gently separate and scan the papers, transcribe the information, and store the originals in an archival manner.

The exciting thing that I have noticed about the few that I have looked closely at, is that there seems to be no other record of the burial.

The set of cemeteries these records are from is quite unique. I am very familiar with them because I am currently writing a book about them called “Galveston’s Broadway Cemeteries” for Arcadia Press. It is due out in July 2015, so I am still finalizing research.

Appearing as one large, two-city-block cemetery, it is actually seven distinct cemetery that have been through a number of grade raisings…therefore losing the location many of the burials.

Using a variety of records, including transcriptions over the years, old photos, plot maps from different sextons and additional “treasures” of information like these slips of paper, we can more fully understand the history of our cemeteries and reconstruct who is at rest there.

PLEASE NOTE: I AM WORKING WITH THE CITY, WHO OWNS THE CEMETERY, TO RESTORE RECORDS. If you are not working directly with the owner of the cemetery, please notify the correct authorities of your discovery for permission to remove (even temporarily) any paperwork from a cemetery.

PLEASE NOTE: I AM WORKING WITH THE CITY, WHO OWNS THE CEMETERY, TO RESTORE RECORDS. If you are not working directly with the owner of the cemetery, please notify the correct authorities of your discovery for permission to remove (even temporarily) any paperwork from a cemetery.

So while transcribing the grave markers in graveyards and cemeteries is vital to saving there history, there are other sources I hope you’ll consider including in your research…and OF COURSE share the results with others!

Let me know what surprises you have found in cemetery research!

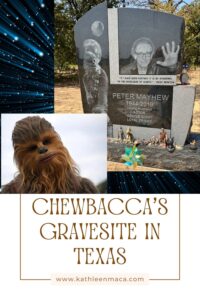

Unfortunately, Mayhew passed away shortly before his 75th birthday. He is buried in Azleland Memorial Park in Reno, Texas.

Unfortunately, Mayhew passed away shortly before his 75th birthday. He is buried in Azleland Memorial Park in Reno, Texas. Azleland Memorial Park is in Parker County.

Azleland Memorial Park is in Parker County.

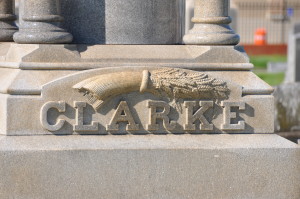

ng holidays, we are surrounded by symbols of harvest and bounty. One of the most popular symbols of the season’s bounty is a sheaf of wheat, which is why it is often incorporated into decorations.

ng holidays, we are surrounded by symbols of harvest and bounty. One of the most popular symbols of the season’s bounty is a sheaf of wheat, which is why it is often incorporated into decorations. The image is so connected with bounty and prosperity that it was at one time used on United States currency.

The image is so connected with bounty and prosperity that it was at one time used on United States currency. Eucharist, a motif of everlasting life through belief in Jesus. Therefore when wheat is used on gravestones or memento mori, it represents a divine harvest – being cut to resurrect the “harvest” into everlasting life or immortality.

Eucharist, a motif of everlasting life through belief in Jesus. Therefore when wheat is used on gravestones or memento mori, it represents a divine harvest – being cut to resurrect the “harvest” into everlasting life or immortality. The wheat sheaf can also signify a long and fruitful life, often more than 70 years.

The wheat sheaf can also signify a long and fruitful life, often more than 70 years.