Tag: San Jacinto

USS Texas – Change of Address

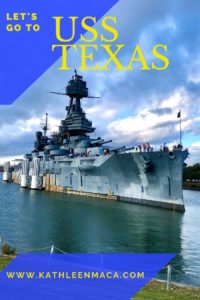

It’s hard to believe that the USS Texas won’t be moored at the San Jacinto Battlegrounds across from the Monument any longer. I’ve been visiting this historic ship here since I was a kid. This is the last weekend that it will be here before heading to dry dock for some much-needed repairs. After that, she’ll go to her new home . . . which hasn’t quite been decided yet.

Now this isn’t just any old ship. Commissioned in 1914 (yep, over 100 years ago), she’s one of the few surviving Dreadnaughts and a veteran of two world wars. That makes the Texas one of the oldest surviving battleships in existence. If you’re at all interested in naval history, hers is worth reading about.

Now this isn’t just any old ship. Commissioned in 1914 (yep, over 100 years ago), she’s one of the few surviving Dreadnaughts and a veteran of two world wars. That makes the Texas one of the oldest surviving battleships in existence. If you’re at all interested in naval history, hers is worth reading about.

Constructed of iron, wood and steel the years and elements have taken their toll and previous “bandaid” repairs aren’t going to help any more. So the state, who owns the ship, has dedicated $35 million to her refurbishment with the understanding that they will no longer pay for repairs. (Yikes!) That’s part of why the ship needs to relocate. It will take a lot more visitors to pay the bills from here on out.

They have installed 750,000 gallons of expanded foam to reduce the water she’s taking on from over 2,000 gallons per minute to under 20 gallons per minute. That should make her stable enough to be towed to dry dock in Galveston for repairs.

After she’s, well . . . ship shape again, she will either be berthed in Baytown, Beaumont or at the Sea Wold Park in Galveston alongside the Stewart and the Cavalla. (I have my fingers crossed for Galveston.)

After she’s, well . . . ship shape again, she will either be berthed in Baytown, Beaumont or at the Sea Wold Park in Galveston alongside the Stewart and the Cavalla. (I have my fingers crossed for Galveston.)

When I found out that my husband (who grew up just about 12 miles away from the San Jacinto Monument Park) had never been aboard the Texas, I decided we needed to take advantage of this “last weekend” to walk her decks. Lots of other locals had the same idea.

In addition to the fascinating things to see on the Texas, including peeks at rarely seen spaces like the officers’ wardroom, Santa was even there – and ya know I can’t resist the guy in red. I even spotted one of those rascally elves in the mess hall. See him hanging on the fridge?

In addition to the fascinating things to see on the Texas, including peeks at rarely seen spaces like the officers’ wardroom, Santa was even there – and ya know I can’t resist the guy in red. I even spotted one of those rascally elves in the mess hall. See him hanging on the fridge?

We came away with “Merry Christmas” Battleship Texas T-shirts – not something you see everyday.

We came away with “Merry Christmas” Battleship Texas T-shirts – not something you see everyday.

Now we’re all going to need some patience to wait during repairs and the decision about her new home. But wherever that will be, I’ll be back aboard when I get the chance.

Now we’re all going to need some patience to wait during repairs and the decision about her new home. But wherever that will be, I’ll be back aboard when I get the chance.

Wounded at San Jacinto – Died at Galveston

I wanted to write a post for Memorial Day that tells the story of someone with Galveston ties who gave their life in battle. The challenge was that there are so very many stories to tell. In the Broadway Cemetery complex alone there are veterans from every war from 1812 forward. Of course, not all of them lost their life in the service, and many of those who did have stories that are well-known.

So I decided to go with a little more obscure story with Galveston ties that many locals may not have heard.

When people visit the San Jacinto Battleground State Historic Site, they usually visit the impressive star-topped monument and possibly the USS Battleship Texas. But are you aware there are actually TWO cemeteries on the grounds?

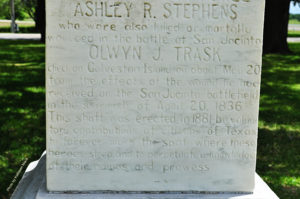

The most visible of the two is close to the battleship, and known as San Jacinto Battlefield Cemetery. It is where the handful of Texans killed in the battle were buried near the Texan Army camp. Buried there are Dr. William Junius Motley, Sgt. Thomas Patton Fowle, Lt. George A. Lamb, Lt. John C. Hale and privates Lemuel Stockton Blakey, Mathias Cooper, Ashley R. Stevens, Benjamin Rice Brigham and Olwyn Trask.

A monument called the Brigham Monument was erected at the gravesite in 1881.

A monument called the Brigham Monument was erected at the gravesite in 1881.

Taking the time to read the lengthy inscriptions, the word “Galveston” (of course) caught my eye.

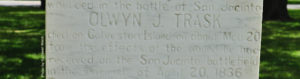

“Olwyn J. Trask…died on Galveston Island… of wounds …received at the San Jacinto Battlefield…”

This is how it begins, folks. I see something like this and I’m off, down the rabbit hole of research. Olwyn’s story took me on a complicated journey that involved his family, his unlikely demise, and even the beginnings of Baylor University. But here, I’ll just concentrate on his story.

Olwyn Trask’s sister Frances was a brilliant educator in Texas. By some accounts Olwyn, a recent college graduate, was sent to Texas during the Revolution by their family in Massachusetts to bring her home. Because he arrived in the Spring of 1835, however, it is more likely that he came to join her and their cousins (the Dix family) to seek out business prospects.

Soon after spirited 21-year-old reached Galveston though, he impulsively joined the Texas Army to fight for independence from Mexico.

He became a member of Captain William H. Smith’s Cavalry Company, after General Sam Houston himself witnessed his horsemanship skills in lassoing a young mustang.

On April 20, 1836, the day preceding the famous Battle of San Jacinto, he was one of 80 men under Colonel Sherman who skirmished against the Mexican Army. Only two men in the Texan ranks were wounded, but Olwyn’s were mortal.

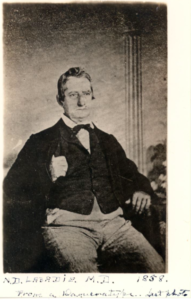

Nicholas Descomps Labadie was an assistant surgeon in the Second Regiment Volunteers under Anson Jones, and treated Trask when he arrived back at camp. The conditions were primitive, and resources limited.

Nicholas Descomps Labadie was an assistant surgeon in the Second Regiment Volunteers under Anson Jones, and treated Trask when he arrived back at camp. The conditions were primitive, and resources limited.

Olwyn was transported to Galveston on a boat with Texan President Burnet and others, where he was to receive further treatment.

The following extract of a letter from New Orleans furnishes details of Olwyn’s fate:

“I called on General Houston yesterday, to ascertain particulars relative to Olwyn J. Trask; he says that he lies dangerously wounded at the Fort at Galveston Island. His thigh was broken in a charge made by 80 of our calvary on about 250 Mexicans, on the 20thof April, in which he behaved most gallantly. He fell from his horse when the ball struck him, but was almost instantly seen again supporting himself on one leg by his horse and had the satisfaction to kill the man who shot him. This was confirmed by one of the aids of General Houston, then present, who remarked that he was in a position to see the whole of it. He said that after Olwyn had laid the man dead at his feet, he sprang on his horse again, in the midst of the enemy’s cavalry, his own corps having retired and immediately urging him to his utmost speed, cutting his way through the ranks, and brandishing his sword at everything that opposed him, when, as the Aid remarked, they seemed to open for him to pass, and he entered the camp with his leg swinging like the pendulum of a clock.”

Olwyn’s thigh bone had been shattered. It was generally believed among those present that if he had received expert medical attention from the start he might have lived. The makeshift facilities are blamed for his demise about three weeks after the battle.

Upon his death he was buried with his comrades “with all the honors that could have been paid to the Commander in Chief; all the troops were under arms, and the officers of the Navy joined in the procession and minute guns were fired during its progress to the place of burial.”

Olwyn J. Trask’s name and gallantry were so revered in his home state of Massachusetts that young men went so far as to legally change their name to his.

In the years that followed, a community cemetery grew around these graves, but now part of the 10-acre site is partially covered by a parking lot for the battleship.

The deed records of Harris County shows that on November 2, 1837, Frances J. S. Trask, Olwyn’s sister, was living at Independence, Washington County, Texas and was on that day appointed representative of Israel Trask of Massachusetts, who was heir to the property of his deceased son. She was awarded the 640 acres of land due Trask’s services at San Jacinto, and used some of it to build a school. This school was the root of what would eventually grow into Baylor University.

Memorial Day seems an appropriate time to remember this young man,

and so many others, who have given their lives fighting for their beliefs and country.

Happy San Jacinto Day!

Oscar Farish was born on December 18, 1812, in Fredericksburg, Virginia, and emigrated to Texas in October, 1835 to pursue his profession of land surveyor. He joined Captain McIntyre’s Company of Col. Sidney Sherman’s Regiment, and participated in the Battle San Jacinto. He was one of the last surviving veterans.

Oscar Farish was born on December 18, 1812, in Fredericksburg, Virginia, and emigrated to Texas in October, 1835 to pursue his profession of land surveyor. He joined Captain McIntyre’s Company of Col. Sidney Sherman’s Regiment, and participated in the Battle San Jacinto. He was one of the last surviving veterans.

In 1837 he was elected engrossing clerk of the First Congress of the Republic of Texas. Mr. Farish was elected to be the first Clerk of Galveston County in 1856 and was holding that office when he died May 25, 1884.

Farish and his wife rest in Galveston’s Old City Cemetery, one of

locations included in “Galveston’s Broadway Cemeteries,” releasing in July from Arcadia Publishing, and available for pre-orders on Amazon.